Evolution of the Chinese Script

From a simple, ideo-, and pictographic script to a highly stylized script, Chinese script has evolved dramatically over the years. Eventually, it underwent a change from the perhaps overly complex–albeit very artistic – to the highly simplified before making the shift to a Latin-based (Romanized) script.

It could help the Chinese government's efforts to eradicate illiteracy. And also make the Chinese language much more accessible to a foreign audience.

Since the Romanized script made it possible to say pronunciation with the help of diacritical markings familiar to several Western languages.

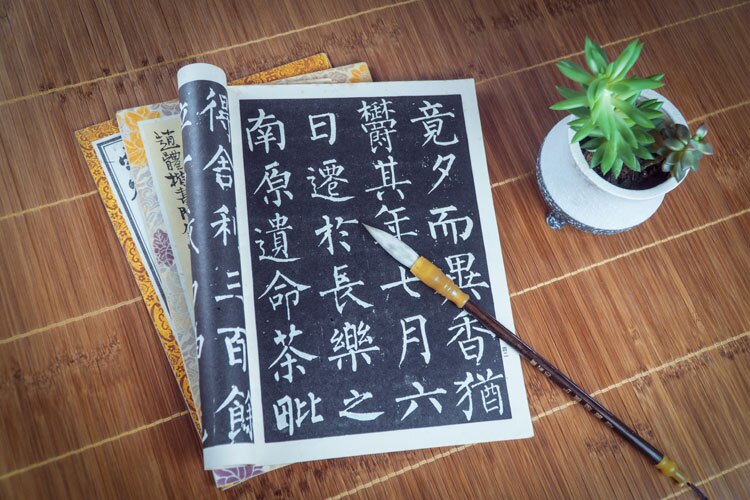

Chinese Script Evolution Diagram

The table diagram below, replete with supplementary information. It depicts the progression of the Chinese script from its earliest, ideo-, and pictographic forms to its final form before the leap to a Romanized script.

Bypassing the somewhat dead-end attempt to create a simplified phonetic script that did not rely on Romanization. E.g. the Zhuyin Fuhao script (aka Bopomofo), which never quite caught on. See the section on indigenous, Latin-inspired – but not Romanized - transliteration systems below.

Comments to the above Chinese script evolution diagram:

The Oracle-Bone script – the earliest known Chinese script. It was highly pictographic in nature and dated back to the Shang (BCE 1700-1027) Dynasty period.

The Bronze script – traces back to the late Shang Dynasty/early Western Zhou (BCE 1027-771) Dynasty period. Its creation stems from the fact that a more graphic type of script was needed for inscriptions on metal objects (tools, weapons, and utensils).

During the period in question, these objects were mainly made of bronze, hence subsequently the name was given to the script.

The Large Seal script – is dated to the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (BCE 770-221). It is subdivided into the Spring and Autumn Period (BCE 770-476) and the Warring States Period (BCE 475-221). It was also used primarily on bronze objects.

Seen in retrospect, it represents an intermediate stage between the older script styles of the preceding era and the newer, "cleaner" scripts that would be introduced with the Qin Dynasty (BCE 221-207), China's first Imperial dynasty.

The Small Seal script – stems from the Qin (BCE 221-207) Dynasty.

Just as Qin Shi Huang unified China on the heels of the troubled Warring States Period of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, declaring himself the emperor. Qin Shi Huang also undertook to standardize the Chinese script, and thus was introduced the Small Seal Script.

In fact, the number of achievements of this short-lived dynasty is rather amazing, but as any psychologist will tell you, zealousness. Qin Shi Huang was apparently a very zealous man.

Perhaps a micro-manager type in today's parlor which often leads to failure. Or, to put it slightly differently, one's greatest quality oftentimes proves to be one's Achilles heel.

The Clerical script – owes its roots to the Small Seal script, according to historians. That said, it bears little resemblance to that script, at least to the layman.

In fact, one can say that the Clerical script marks a turning point in the evolution of the Chinese script away from the pictographic and toward the more stylistic.

The Clerical script made its appearance during the 1st century BCE, or during the Western Han Dynasty (BCE 206 – CE 009). But it came into prominence first during the Eastern Han Dynasty (CE 25-220).

It has also been nicknamed the "Breaking Wave" script due to the bold. Sweeping curvature of its downward-sloping strokes (seen in the above diagram in the characters for "horse" and "to see").

Note also that the Simplified script would revive this "breaking wave" feature almost to the point of exact replication.

The Grass script – aka Cursive script, was, in all likelihood, conceived sometime in the 3rd century CE, i.e., during the Eastern Han (CE 25-220) Dynasty.

There is some murkiness over the exact period of the emergence of the Cursive script. Just as there is murkiness surrounding the exact period of the emergence of the Semi-Cursive script (see below).

With some sources claiming that the latter script preceded the former. Though most sources, in contrast to the more dubious sources, cite references – claim that the Cursive script arrived first.

The confusion is understandable. For, with the cursive scripts (cǎo shū), we have for the first time in Chinese history a script type that served a dual purpose. The usual means of writing and, additionally, a means of artistic embellishment.

The first cursive script- to see the light of day (zhāng cǎo), served the usual function as a medium of writing. That it was not very fanciful, being instead of a hurried, or shorthand, way of writing the main script of the day, the Clerical script.

But on seeing this more flowing, more comely script, others – being more aesthetically than practically oriented – saw in it a vehicle for artistic expression.

Thus the later, more fanciful cursive script that would emerge (jīn cǎo) possibly existed parallel, at least for a time, with the less fanciful version. This less fanciful cursive script would be superseded by a more deliberate.

The in-between script whose function was if not that of writing, the Semi-Cursive script described further below.

So it seems, that the less fanciful script, the zhāng cǎo script, emerged during the latter part (around the turn of the 3rd century CE) of the Eastern Han Dynasty.

While the more fanciful variant, the jīn cǎo script, came into prominence during the Kingdom of Wei (CE 220-265, aka Cao Wei Dynasty) Period. One of the famous three parallel kingdoms of the Three Kingdoms Period (CE 220-280) that followed on the heels of the Eastern Han Dynasty.

Note that the Chinese language non-cursive versus cursive comparison to printing versus handwriting in Western languages is valid. As long as we are speaking of ancient China when each word consisted of a single syllable character.

The building blocks of, say, the English language are the letters of the alphabet. While the building blocks of the ancient Chinese language are the strokes of the alphabet. See the diagram above depicting the 12 standardized strokes.

Since the strokes of the Cursive script flow together as do the letters of the English word. The comparison is quite apt as regards a single Chinese syllable character. Though the comparison breaks down as regards polysyllabic Chinese words. Since each character-syllable stands alone are not connected.

The Regular script – aka Standard script. Since it became the standard, it is still used today to represent the traditional Chinese character.

It appeared either at the end of the Eastern Han (CE 25-220) Dynasty or during the subsequent Three Kingdoms (CE 220-280) Period.

The Regular script is considered the most readable (i.e., legible) style of traditional Chinese script hitherto produced. It is the traditional Chinese script that is adapted to – i.e., made compatible with – all commonly-used modern Chinese fonts, including the font used to write this article.

But, many sources say that the regular script first appeared during the Wei Dynasty (220-265 AD). It is also suggested that the semi-cursive script (see below) originated in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD).

It is a compromise between the cumbersome (slow) Regular Script and the almost illegible Cursive Script. The first variant of the cursive script also appeared in the Eastern Han period.

The chronology of this defies logic since this would mean that the Regular script. It is supposed to have inspired the creation of the Semi-Cursive script, but it came after the Semi-Cursive script.

The Running script – aka Semi-Cursive script. According to most sources, it was developed during the Eastern Han (CE 25-220) Dynasty.

While most insist that it was developed as a compromise between the cumbersome Regular script and the illegible Cursive script. They suggest a chronology for the creation of these three scripts that defies logic (as per the note above).

Maybe, Semi-Cursive script was not created in response to either the illegible Cursive script (the

jīn cǎo script) or the cumbersome Regular script.

It was simply a further extension of the earlier, prototype Cursive script, the zhāng cǎo script. The only function of it was writing (i.e., requiring legibility), not an embellishment – albeit, speed writing, as it were.

If we take this route, then we avoid the trap of illogical chronology. It is also a much more satisfying explanation since it links back to the original raison d'être of the very first cursive script, a rapid form of writing.

Imagine it for a moment... a shorthand form of writing is developed. After that, it is taken over by a group of artistic souls (calligraphers) who care not a whit about legibility. And what was supposed to be a shorthand form of writing has instead become an altogether different animal!

Considering this practical background, there is a very reasonable guess. Someone interested in writing as a medium for verbalization, rather than being interested in the art of calligraphy. He decided to revive the original shorthand form of speed writing, thus the Semi-Cursive script was born.

Note, but, that calligraphers also cast themselves over even the Semi-Cursive script!

In fact, one of the most famous Chinese calligraphers, Wang Xizhi, lived during the Han Jin Dynasty (CE 265–420). He wrote his celebrated literary work, Preface to the Poems Composed at Orchid Pavilion, in the Semi-Cursive script.

So the Semi-Cursive script ended up serving at least a dual function. it means that in spite of being employed by calligraphers, it could still be read!

The Simplified script – is a modern script that stems from 1949. It can be seen as a halfway step toward the creation of the later-to-come Romanized Pinyin script.

While it was quite short-lived, it at least provided the impetus. As indicated, developing a thorough script system that would make it easy for even uneducated people to learn to read and write.

In fact, one could reasonably argue that if simplified characters had not been developed in 1949, Pinyin would probably not have been developed as early as 1958.

Many of the ancient scripts depicted above are still current. Even they are only for very specialized uses. For example, the Large Seal script is commonly used today for shop signs. It is additionally seen in certain calligraphic applications.

While the Small Seal script is used in smaller applications. Such as for name tags and seals, for logos on stationery, but also for certain calligraphic applications. The Clerical script is used both for shop signs and logos, but also on the headers of stationery.

The Grass script, aka Cursive script. It remains one of the most popular Chinese scripts for calligraphic applications. This is understandable. This applies to a large extent to the Semi-Cursive script as well.

The Regular script is still the most common font for writing traditional Chinese characters to this day. And, as we saw above, it is now integrated into all common Chinese fonts used in software applications.

Latinization and Its Influence on Chinese Orthographic Conventions

From what we know about Chinese characters during the Han Dynasty, if not earlier, Chinese was written from right to left, in columns, not rows. Chinese characters are designed to occupy equal space in two dimensions, regardless of their actual size.

Thus, Chinese characters are like blocks stacked one on top of the other. The initial character in each column is located at the top of the column.

To read an ancient Chinese text, read the rightmost column from top to bottom, and then read the columns from top to bottom, top to bottom, and left to left, etc.

China's contact with the outside world, especially with the Europeans, influenced Chinese orthography.

This is because the European language writes from left to right in rows, not columns. This is because it is impractical to add loanwords to the standardized columns reserved for Chinese characters. Latin-based words (some of which can be quite long).

Moreover, each Latin-based word is written from left to right. A word in a traditional Chinese text which writes from right to left, albeit, in rows, was a bit jarring.

Thus traditional Chinese texts eventually came to be written in the same manner as Latin-based text: in rows, from left to right.

The traditional method of Chinese orthography, i.e., of writing in columns from right to left and from top to bottom, is still practiced in Taiwan.

But, if this practice reflects resistance to language practices in the mainland of china for ideological reasons, it is likely to change over time, for practical reasons.

Foreign-Introduced Latin-Based Transliteration Of Traditional Chinese

It is widely believed that the Portuguese Jesuit missionary duo Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri were the first to attempt to transcribe Chinese syllabic characters into the "Western" (Latin/Roman) alphabet. Phonetic symbols (variant marks, etc.) were used to capture the tones of traditional Chinese syllabic characters.

While this is apparently true, there is an even earlier effort to transcribe the Chinese syllable character to a foreign language.

The first Buddhist monks to arrive in China from India commenced shortly thereafter to translate their Buddhist texts from Sanskrit to Chinese quickly.

They discovered certain structural regularities in the spoken Chinese language. Such as an "initial sound", a "final sound" and a "suprasegmental tone". They characterized the pronunciation of the Chinese syllable character.

It is conjectured that this knowledge formed part of the foundation of the late. But not much later, for we are still in China's ancient, Three Kingdoms (CE 220-280) Period.

The universal phonetic system called Fanqie. It is a system that illustrates the pronunciation of unknown orthographies. With the help of snippets–often resorting to rhymes as a pronunciation aid – of known (to the audience in question) orthographies.

As an example of a modern-day Fanqie, imagine a Danish speaker wishing to explain to an English speaker the pronunciation of the surname of Connie Hedegaard.

She was the President of the 2009 UN Climate Conference in Copenhagen and a former Danish government minister. Now she is the EU Commissioner for Climate Action.

The Danish speaker might say that the "Hede" of "Hedegaard" is pronounced like the "heath" of "heather" (which is decidedly not pronounced like the "Heath" of "Heathcliff", the protagonist in the 19th-century English novel Wuthering Heights!).

But, as part of the cultural "trade", Buddhist monks who arrived in China discovered the structural patterns of spoken Chinese.

It spread from east to west and from west to east again along the Silk Road when applied to later-era. The polysyllabic spoken Chinese, such as Mandarin. In ancient China, as mentioned above, most words consisted of monosyllabic characters.

Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri, the Portuguese Jesuit missionaries mentioned earlier. They developed the first unified system for transcribing Chinese "words" into Latin.

They prepared for their joint work on a Portuguese-Chinese dictionary. They developed the first unified system for transcribing Chinese "words" into Latin. The Latinized transcription of Chinese and the later compilation of the Portuguese-Chinese dictionary were undertaken in the period 1583-88.

Although the manuscript was never published in book form. It eventually found its way somehow into the collection of the Jesuit Archives in Rome, where it was not rediscovered until 1934. It will be published in book form as early as 2001.

Ricci and another Jesuit colleague, Lazaro Catanio, compiled a dictionary in the winter of 1598. It was a reverse dictionary from Chinese to Portuguese. This utilized a comprehensive system of variant symbols as a guide to tonal pronunciation.

Unfortunately, the manuscript of this work was lost, but it may surface someday.

Fortunately, Catania was the driving force behind the aforementioned comprehensive transcription system of the Chinese-Portuguese Dictionary. But unfortunately, it has disappeared. He produced a separate manuscript of his comprehensive transcription system.

It was a manuscript that would later be used by the Polish Jesuit missionary to China, Michał Boym. He translated the first Latinized version of the Nestorian Stele (the Nestorian Tablet), with two Chinese assistants. The Tang (CE 618-907) Dynasty period Stele appeared in China Illustrata in 1667.

It was an encyclopedic work that was compiled by the German Jesuit scholar, Athanasius Kircher.

The most famous Chinese name in history, Confucius, sorry if you thought it was Mao Zedong! It is just such a Latinized transcription that can be broken into four parts.

Con, a Western sound bastardization of the Chinese family name. Kong, common in the ancient province of Canton (Guangdong). Fu (the same as in the other Latinization transcription systems). Ci (tzu, zi or dz in other Latinization transcription systems). Us, which is strictly a Latin suffix indicating a masculine noun.

Since fu-ci means "grandmaster", Confucius can be translated as "Grand Master Kong". Another famous Confucian, Mencius, is the Latinized version of "Master Meng".

Another well-known Latinization system for the Chinese is the Wade-Giles system. This system is named after Sir Thomas Francis Wade, a British diplomat and sinologist. He prepared the Beijing Dialect Syllabus in 1859.

It is a Romanized phonetic system full of tonal representations. Designed for the Beijing dialect. Herbert Allen Giles expanded the Beijing syllabary into a complete transliteration system in 1892. The system rendered Mandarin Chinese into a Romanized alphabet

The Wade-Giles system was the first widely accepted Chinese-Romanized phonetic system. Its main drawback is in its pronunciation symbols. It relies partly on the superscripted numbers.

And many smaller publishers were not sophisticated enough to handle the superscripted text. The result is that the numbers are either omitted or rendered in plain handwriting. This, of course, defeats the purpose of numerical superscripts as pronunciation guides.

As a result, the Wade-Giles system became less attractive as a universal phonetic medium. Even though it is still widely cited today.

Without going into detail, other Chinese-to-Romanization transliteration systems include the 1902 EFEO (Ecole Francaise d'Extreme Orient) system.

The so-called Postal system, which borrowed perhaps from the EFEO system since it was based on the French style of Romanization (it was used exclusively to render Chinese place names into a Romanized alphabet precisely for postal purposes.

We should remember that after the mid-nineteenth century, much of China was under the influence of foreign powers. This was the result of many international treaties. Those involved trade and territorial concessions in Hong Kong imposed on the Qing government.

For example, Hong Kong and Macau, as well as parts of Shanghai, Qingdao, and other larger port cities.

The Yale system was developed at Yale University in the US. It was an aid to communication between the Allied military and Chinese resistance forces during the WWII-era. At that time, Japan occupied much of China.

The Protestant movement in China also developed a very comprehensive phonetic system to deal with many of the local languages encountered by Protestant missionaries. This was because, in most rural areas of southern China, people were not familiar with either Mandarin or Cantonese.

Protestants also made use of the romanization system developed by James Legge. He was a Scottish sinologist and Protestant missionary who served in China in the latter half of the 19th century.

The Wade-Giles system mentioned earlier actually built on the progress inherent in the phonetic system developed by Legge.

The Chinese eventually developed their own phonetic system. Using the Latin alphabet. It often referred to as the Roman alphabet at this time, although earlier.

For example, at the time when Portuguese Jesuit missionaries had arrived in China, Latin was still an active written language or a Latin-inspired alphabet. Of course, all these transliteration systems, including those native to China, build on the advances that preceded them.

Indigenous Latin-Inspired Transliteration Of Traditional Chinese

The first indigenous Chinese Romanization system was the Qieyin Xinzi ("New Phonetic Alphabet"). It was developed by a certain Lu Zhuangzhang in 1892. The Qieyin Xinzi system was specifically developed to render the phonemes of the Xiamin dialect of the Minnan ("Southern Min") language to a Romanized alphabet.

Here again, earlier work surely influenced the author. It would be very strange indeed if Lou didn't realize/didn't see the romanization system of Catanio, Wade, Giles, etc.

Together with Wu Jingheng (the founder of the so-called "Bismuth alphabet") and Wang Zhao (who developed the "official character list" in 1900), Lu was one of the three members of a committee. Their task was to develop a special system of Chinese phonetics.

This system did not strictly belong to the romanization system. Even though it imitated such a system in its phonetic structure, which later became known as Zhuyin Fu, or Bopomofo. The latter refers to the first four character names of the system: ㄅ, ㄆ, ㄇ and ㄈ.

In 1923, China's own Ministry of Education established the National Committee for Language Unification. There were five prominent scholars.

One of them was the famous Chinese-American linguist Zhao Yuanren. He is the author of the humorous monosyllabic story "The Lion Eater". In his writings, he used only the syllabic word "shi".

After a year of deliberation and investigation, the committee decided to develop a romanized transliteration system. The committee decided to develop a romanization system. In 1928 it presented their results, namely, the Kougyou Romance system.

This system is different from the previous romanization phonetic system. It does not rely on either the pronunciation symbols or the numbers in the superscript. Rather, it provides variants on the romanized letter spellings of syllabic roots.

To reflect the fact that the sound variations inherent in different Chinese syllables are spelled the same in other phonetic systems. Except that variant symbols or numbers are added to the superscript (in the case of near-syllabic homophones).

As a direct result of this, the Gwouyeu-Romatzyh system can be written using a standard QWERTY keyboard. This also makes it available to all publishers, regardless of their complexity.

Despite these promising features, and the creators' desire to see it completely replace Traditional Chinese, the Gwouyeu-Romatzyh system never caught on with Chinese users.

Unless it was used in dictionaries to aid in the pronunciation of certain difficult Chinese characters. Perhaps the Gwouyeu-Romatzyh system was ahead of its time.

The Soviet Union tried to develop a universal romanization system for all Chinese, the Latin-Syngwen system. It's about a decade after the Russian Revolution (1917). This system is completely independent of intonation.

Like the ancient Roman system, the Latin-Sinwine system had the ambition to replace Traditional Chinese and other Sinitic languages completely. In 1931, a joint group of Russian and Chinese expatriate scholars living in Moscow was formed.

The Latin-Sinwenz system was developed to bring literacy to a large number of Chinese speakers. The people lived in the eastern part of the Soviet Union.

The Latinxua Sinwenz gained some popularity. It was welcomed by prominent Chinese intellectuals such as Lu Xun and Guo Moruo. From 1940 to 1942, it was introduced into the Soviet-controlled western provinces of China (the Shaanxi-Gan Ning region).

This was despite the fact that the Northeast Chinese railroad system had adopted the Latin-Semitic system as early as 1949. But the Latin-Swedish system had already sounded its death knell in 1944.

The Communist Party of China returned the Soviet-occupied western China (Shaanxi-Gan Ning region), which had been under the rule of the Republic of China (Kuomintang). Warlordism was especially prevalent in western China.

The Chinese communists stopped the spread of the Latin-Singwen writing system to please the local people living under Soviet rule. Reverted to traditional Chinese and traditional regional variants of Chinese. In fact, these people were unhappy with the Soviet-imposed Latin-Singwen writing system and its "foreign" orthography.

But, the Chinese communists themselves would soon develop a similar romanization system. The Pinyin system is now widely accepted. It would not only borrow heavily from the previous Roman and Latin phonetic systems. But It would also include some of the key linguists. It helped develop those earlier romanization/Latinization systems.

Wu Yuzhang, Ni Haishu, and Lin Handa, all co-developers of the Latinxua Sinwenz system. Li Jinxi and Luo Changpei, both co-developers of the Gwouyeu Romatzyh system. They worked together with Zhou Youguang.

Zhou lived and worked in Japan and the US until he returned to China in 1949. He was a distinguished economist, administrator, and former banker. And he was also a self-styled hobby-linguist.

They developed the Pinyin transliteration system during the period 1955-58. Zhou Youguang is generally regarded as the "Father of Hanyu Pinyin".

It must be noted, but, that the committee of linguists established under the leadership of Zhou Youguang made every effort. Perhaps understandably, they developed a system of phonetic transliteration inspired by the Latin language.

It does not rely directly on the Latin alphabet instead. But former Premier Zhou Enlai, in his 1958 speech, announced the creation of Hanyu Pinyin. The committee spent three years trying to avoid the direct use of the Latin alphabet.

But since "no satisfactory results were achieved. At that time, the Latin alphabet was adopted.

The former premier went on to say, "In the future, our Hanyu pinyin will use the Latin alphabet. It has a wide range of applications in the field of science and technology. And it is often used in daily life, so it is easy to be remembered.

Thus, the adoption of this alphabet will greatly contribute to the spread of the common language."

It is claimed that Chairman Mao (Mao Zedong), like many others who were early adopters of the Latin phonetic system. He firmly believed that Hanyu Pinyin (today abbreviated as Pinyin) would completely replace all other forms of Chinese, including traditional Chinese.

As we now know, this did not happen.

In fact, during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76), Pinyin disappeared completely from the mastheads of the People's Daily and Red Flag (Hong QI) Journal. Since 1958, Pinyin has been used as a subtitle for translations. All official newspapers continued to publish headlines in traditional Chinese characters.

Attempts at further improvements to Pinyin (completed and published in 1977) were completely rejected a few years later. As a result, Pinyin reverted to its original form in 1949 in 1986.

Meanwhile, Pinyin was recognized as the official standard for traditional Chinese by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in 1982.

Curiously, Pinyin gradually incorporated the "initial, final, and superlative" pattern. This is the earliest form of Chinese - consisting of monosyllabic words. This is what the first Buddhist missionaries (monks) said when they arrived in China from India.

Today, other, albeit informal, Latin-based or Latin-inspired phonetic systems are used. To translate lesser Chinese languages such as Cantonese into a more modern and friendly form. One of these efforts is the translation of Cantonese into the written language.

As an online chat and instant messaging language, it has become quite popular among Hong Kongers and other Cantonese speakers. Although its use is limited to informal, non-face-to-face settings.

Similarly, other informal manifestations of spoken minority languages exist in written form.

For example, the Nüshu script of the local Chinese dialect "Xiangnan tuhua". It is spoken by people in the Xiao and Yongming River areas in the northern part of Jiangyong County, Hunan Province. It is called "women's writing".

People in this area are bilingual and can speak in the Mandarin dialect common in southwest China. When they feel the need to write in the official Southwestern dialect, they always write in traditional Chinese characters rather than in the local Chinese dialect of Nüshu.